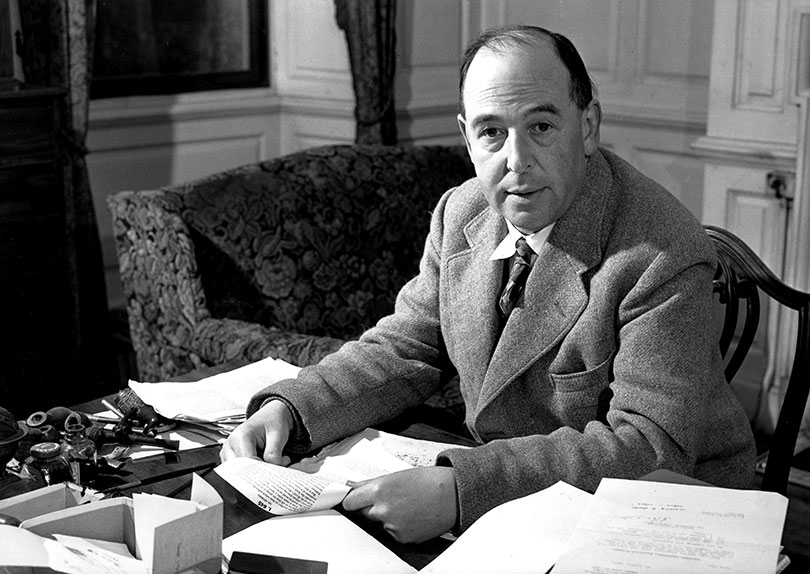

C.S. Lewis as Christian Political Philosopher: The Politics of Skepticism and Liberty

by Robert Schwarzwalder

Ph.D. cand., University of Aberdeen (history)

Senior Lecturer, Regent University

February 2020

A few days before his death in 1963, C.S. Lewis wrote to Mrs. Frank Lewis, an American admirer, that politics is ‘a subject in which I cannot take any interest’.1

Those who knew him best, including his brother and his stepson, affirmed not only his disinterest but even his contempt for political action. 2

So it is with some hesitation that I begin an article on C.S. Lewis by disagreeing with my subject.

To the point, his claim that he found politics uninteresting is unconvincing. On the contrary, Lewis thought a good deal about public life, politics, and how those responsible for the public good should behave.

The historian A.J.P. Taylor wrote that at Oxford’s Magdalene College, ‘Lewis helped in the history school by teaching political theory … His lectures covered Rousseau and Aristotle, et al. He loved doing this’. Lewis was a firm opponent of what he called ‘Bolshevism’ and, write Lewis scholars Justin Dyer and Micah Watson, ‘even as a literary scholar Lewis continued to teach his students Western political thought beginning with Plato’. 3

Dyer and Watson go on to note that ‘We know from Lewis’s personal letters, his education and teaching, and his published works that he was both very interested in and knowledgeable about politics and political thought’. Lewis, they rightly argue, ‘had much to say about the foundations of a just political order’. 4

A Critical Distinction

The key to understanding Lewis’s beliefs about public life is to recognize the sharp line he drew between his public commentary and his private opinions. He had strong views about politics, the state, and public justice. But in his public writings and lectures he did not pay much attention to the political issues of the moment. One would be hard-pressed to find anything Lewis wrote for publication or any lectures he gave about Clement Atlee’s defeat of Winston Churchill or Anthony Eden and the Suez Crisis. As Lawrence Reed notes, ‘Lewis’s commentary on political and economic matters is comparatively slim—mostly a few paragraphs scattered here and there, not in a single volume’. 5

Yet in his private correspondence, it’s clear that Lewis read the news of his day with keen interest. In the same letter to Mrs. Jones in which he professed disinterest in politics, he criticizes the Labor government pointedly. In other personal letters, Lewis discusses ‘elections, unions, communist advances in China and Hungary, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and other political topics of the day’. 6 That’s a rather broad swath of political discourse.

This is not to say Lewis especially enjoyed reading about or commenting on, let alone participating in the politics of his time. ‘Why should quiet ruminants like you and I have been born in such a ghastly age?’ he wrote his brother in 1940.

How I loathe great issues. How I wish they were all adjourned sine di ... Could one start a Stagnation Party – which at General Elections would boast that during its term of office no event of the least importance had taken place? 7

On the other hand, to his public, Lewis commented almost exclusively on the moral implications of issues that related directly to Christian ethics and the natural law. For example, he spoke about such things as the state’s role in punishing crime, private ownership of property, euthanasia and experimentation on animals for research purposes.

In other words, he was occupied in his public ministry with issues of moral importance, not extemporaneous political interest. So, human dignity and eternal value were the chief occupations in his commentary about political and social concerns. As John G. West, Jr. writes,

When Lewis talked about these matters, however, it was not in the way most politicians do. He was wholly unconcerned with what political scientists today like to call ‘public policy’—that conglomeration of compromise, convention, and self-interest that forms the staple of much of our own political diet. If you expect to find a prescription for solving air pollution or advice on how to win an election, don’t bother reading Lewis. He has nothing to tell you. His concern was not policy but principle; political problems of the day were interesting to him only insofar as they involved matters that endured. 8

Was Lewis a ‘Red’ or a Card-Carrying Conservative?

Due to his prominence and influence, some on the Left are eager to claim Lewis as their own. At the same time, we need to recognize that Lewis was not a public partisan.

First, was Lewis, in fact, a closet man of the Left? Would he, were he with us today, wear a Che Guevara tee shirt beneath his tweed jacket? A Canadian professor named Mervyn Nicholson argues that Lewis was what he calls a ‘Red Tory’, a conservative ‘in the old sense … Lewis believed in community and mutual obligation, in tradition, in democracy and tolerance’. 9 In other words, reading between the lines, there is little doubt Lewis, were he alive, would have a Bernie Sanders for President sticker on the bumper of his aging Volvo.

Indeed, Nicholson claims, ‘everything (Lewis) says about capitalism is negative … He was anything but a cheerleader for capitalism. His references to capitalism … are critical, often hostile. He did not believe that Christianity was the same as capitalism. He did not believe that Christianity had anything to do with material success … He had zero sympathy with right-wing ideology … Lewis was simply not right-wing … Lewis’s political and economic views were hardly right-wing. Far from being a reactionary social conservative, Lewis had strong radical impulses’.

Reading Dr. Nicholson, I am reminded of a small child stomping his foot and demanding more ice cream. In his view, apparently, repetitive insistence carries the rhetorical day. We might hope that Dr. Nicholson will, in the future, expand on this novel theory of mass persuasion.

What becomes clear in his public and, most especially, private writings is that Lewis was a conservative in a more traditional sense. An advocate of privacy and private property, order and limited government, Lewis represents not a ‘Red Toryism’ but a more Burkean understanding of the role of personal virtue, natural law, and a modestly-sized state. 10

Lewis and Socialism

Contra Dr. Nicolson, Lewis was deeply wary of socialism. He regarded it is a massive failure economically and a danger to the liberty of the people. As Robert C. Stroud writes, Lewis ‘was correct about the propensity of socialism to undermine order and dishevel systems of proven success’. 11

For example, in 1954, after the Conservatives were again in power, Lewis had an exchange of letters with an American admirer named Vera Gebbart. As the U.K. had retained its rationing system long after the conclusion of the Second World War, Mrs. Gebbart and her husband had from time to time sent food packages to Lewis and his brother Warnie.

Here is what Lewis wrote her about the glories of the life under the British Labour Party:

I’m afraid it would be sheer dishonesty to pretend that we now have any kitchen needs; this (Conservative) government has done a magnificent job in getting us on our feet again, and a few weeks back, we solemnly burnt our Ration Books. Everything is now ‘off ration,’ and though at first of course, prices went up with a rush, they are now dropping. But cheer up, if our friends the Socialists get back into power, you will be able to exercise your unfailing kindness once more by supplying us, not with little luxuries, but with the necessities of life! 12

So, Nicholson’s reduction of Lewis to being a chip-on-his shoulder mugwump, a nonconservative conservative with a bias against the Right, is a caricature. Lewis was not anti- capitalism. He was against the abuses of capitalism, which was consistent with his general wariness of concentrations of power.

This theme – the danger of political power – runs throughout Lewis’s novels and his commentary, publicly and privately, as we will discuss more in a moment.

Lewis the ‘Mere Conservative’ Non-Partisan

However, even as Lewis disdained the radicalism of the Left, he was very careful about not being ‘captured’ by the Right.

In 1951, after six years in yet another of his political wildernesses, Winston Churchill returned to Britain’s premiership. Shortly thereafter, he wrote C.S. Lewis and offered him the title, ‘Commander of the British Empire’.

‘Commander of the British Empire’, or CBE, is a mid-range honor. It’s employed by politicians to recognize people who have demonstrated excellence in their field of endeavor.

Yet as with any honor given by politicians, the CBE can also be a way of associating with a popular or esteemed person to the politician’s advantage.

Lewis 13did not want to be identified with any political movement or party for fear this would diminish his public ministry. Once a public figure is ‘owned’ by a party or a politician, a substantial part of the public will write him or her off.

So, in response to Churchill’s offer, Lewis wrote Churchill’s secretary that although he appreciated the offer, ‘There are always knaves who say, and fools who believe, that my religious writings are all covert anti-Leftist propaganda, and my appearance in the Honours

List would of course strengthen their hands. It is therefore better that I should not appear there’. 13

Lewis scholar Philip Vander Elst writes that Lewis was a ‘political and cultural conservative in the widest and deepest sense of the word’. Lewis’s Cambridge colleague George Watson confirmed this, writing some years ago that Lewis ‘believed in democracy and private enterprise for the most grudging of all reasons: though they are much less than good, every other system is worse’. 14

Evidently Lewis’s pro-Western leanings were sufficiently known, at least among some of Britain’s political and religious elites, that the Bishop of Chichester, George Bell, proposed that

Lewis write a book about the threat of communism. He suggested this to Francis Ralph Hay Murray, director of the Foreign Office Information Research Department, as Murray believed that ‘the Church leadership was not up to the demands being placed on Christianity by the Cold War. He had “a nasty suspicion that the leaders of our Christian thought indeed do not know their dialectical materialism well enough” to ‘”formulate, and to formulate clearly and in terms widely comprehensible, the real opposition of the Christian belief to communism”’. 15 Nothing ever came of this idea, but that Lewis would be considered seriously for the task speaks to the latter’s reputation as an opponent of communism.

With all of this, Lewis was not a partisan. He was sort of a ‘mere conservative’ – a proponent of democracy, an opponent of statism, and a prophet warning of the moral and cultural dissolution he saw all around him.

Lewis’s Political Vision

There are three things about which Lewis was emphatic in his various comments about politics:

- His understanding of human nature and its importance to the way we view human government.

- His consequent antipathy toward utopian schemes and concentrations of political power.

- His confidence in God’s triumph in history.

Human Nature

Lewis’s understanding of politics was closely informed by his biblically-rooted beliefs about the fallenness and dignity of all people.

In an article written for Britain’s Spectator magazine in 1943, Lewis wrote, ‘I am a democrat because I believe in the Fall of Man … I don’t deserve a share in governing a hen-roost, much less a nation. Nor do most people who believe advertisements, and think in catch-words and spread rumors. The real reason for democracy is just the reverse. Mankind is so fallen that no man can be trusted with unchecked power over his fellows. Aristotle said that some people were only fit to be slaves. I do not contradict him. But I reject slavery because I see no men fit to be masters’. 16

This is a recurrent theme in Lewis’s writings. ‘Fallen man is not simply an imperfect creature who needs improvement: he is a rebel who must lay down his arms’, he wrote several years later in Mere Christianity. 17

It was for this reason, writes Benjamin Hutchison, that ‘the man who gave us Narnia also mounted firm opposition to the progressive-leftist ideals that swept swiftly across the world stage in his time. Lewis’s resistance to European progressivism was, first and foremost, a reflection on the reality of man’s nature, and the failings of progressivism to account accurately for man’s fallen state. He rejected progressivism’s assumption of man’s inherent goodness, of the state as an idol. Lewis succinctly described progressivism as ‘state worship,’ predicated on the assumption of man’s inevitable rise to god-hood’. 18 Or, as Dyer and Watson write, Lewis disdained ‘the self-defeating modern attempt to conquer human nature’.19

As Lewis wrote in his landmark address, The Weight of Glory, he believed ‘fallen men to be so wicked that not one of them can be trusted with any irresponsible power over his fellows. That I believe to be the true ground of democracy’.

In sum, as Reed writes, Lewis ‘embraced minimal government because he had no illusions about the essentially corrupt nature of man and the inevitable magnification of corruption when it’s mixed with political power’. 20

Yet Lewis’s belief in human depravity was complemented by his affirmation of human dignity.

‘You come of the Lord Adam and the Lady Eve’, Aslan says to the Pevensie children in Prince Caspian. ‘And that’, he says, ‘is both honour enough to erect the head of the poorest beggar, and shame enough to bow the shoulders of the greatest emperor in earth. Be content’.

This is a clear allusion to Genesis 1 and 3, where we learn that our eternal value derives from our image-bearing of God and our fall into sin separates us from Him. As Lewis said in The Weight of Glory, ‘The dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare … There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal’.

Lewis’s belief in man as an image-bearer of his Creator, animated his belief that that equality ‘applies to man as a political and economic animal’.21 This equality meant that no one deserved to be a slave or a serf or a cog. 22

Indeed, as he wrote in Mere Christianity, ‘If individuals live only seventy years, then a state, or a nation, or a civilisation, which may last for a thousand years, is more important than an individual. But if Christianity is true, then the individual is not only more important but incomparably more important, for he is everlasting and the life of a state or a civilisation, compared with his, is only a moment’. 23 This puts not only human value but politics itself in a proper context.

Human dignity included also the rights of independence and personal freedom. Lewis believed firmly in a vision of life in which personal liberty was essential.

In a state that is functioning well, ordinary citizens will be sufficiently virtuous so as not to need or want intrusive governmental supervision. This means a society in which freedom, order, and relative prosperity are the norm. As Lewis describes it in Mere Christianity: ‘The State exists simply to promote and to protect the ordinary happiness of human beings in this life. A husband and wife chatting over a fire, a couple of friends having a game of darts in a pub, a man reading a book in his own room or digging in his own garden—that is what the State is there for. And unless they are helping to increase and prolong and protect such moments, all the laws, parliaments, armies, courts, police, economics, etc., are simply a waste of time’. 23

In sum, then, it was Lewis’s deep understanding of human sinfulness and his concurrent awe at man’s divinely-given dignity caused him to look askance at government.

The Purpose of Government and Skepticism of Power

Since he believed man is made in God’s image but is also fatally flawed, Lewis argued that any concentration of unchecked power was dangerous.

He included theocracy in this understanding. As Lewis wrote in 1958, ‘I detest theocracy. For every Government consists of mere men and is, strictly viewed, a makeshift; if it adds to its commands, “Thus saith the Lord”, it lies and lies dangerously’.24

Put another way, Lewis reposed great faith in God, but was duly wary of those who claim to speak on His behalf concerning issues about which they have no biblical authority or personal expertise. More simply, there is no single Christian perspective on highway improvements or tax rates.

This does not mean that Lewis was not impassioned by the moral component of critical issues. But he drew a distinction between the many issues that demand prudential good judgment and that relative handful whose obvious moral content – for example, euthanasia or the genocide of the Jewish people – about which Scriptural teaching offers definite and undeniable instruction.

Having rejected both statism and theocracy, Lewis argued that the foundation of a good political order was found in the natural law. ‘The very idea of freedom presupposes some objective moral law which overarches rulers and ruled alike’, he wrote in 1943. ‘Subjectivism about values is eternally incompatible with democracy. We and our rulers are of one kind so long as we are subject to one law. But if there is no law of Nature, the ethos of any society is the creation of its rulers, educators, and conditioners; and every creator stands above and outside his own creation’. 25 This is what led Lewis to affirm that natural law was the bedrock of good governance. ‘God, as we know from Scripture (Rom. 2:15), has written the law of just and reasonable behaviour in the human heart’, he wrote in the late 1950s. ‘(Government’s) business is to enforce something that is already there, something given in the divine reason or in the existing custom. … If it tries to be original, to produce new wrongs and rights in independence of the archetype, it becomes unjust and forfeits its claim to obedience.’ 26

This parallels almost exactly the assertion made in the second paragraph of America’s Declaration of Independence: That it is a ‘self-evident’ truth that ‘all men are created equal’, are ‘endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights’, and that it is the purpose of government is to ‘secure these rights’.

In his 1958 article, ‘Is Progress Possible: Willing Slaves of the Welfare State’, Lewis cautioned against ‘an increasingly planned society’ and a ‘mother knows best’ state. In that essay, Lewis asserts that:

The modern State exists not to protect our rights but to do us good or make us good— anyway, to do something to us or to make us something … There is nothing left of which we can say to them, ‘Mind your own business’. Our whole lives are their business. 27

What Lewis in another place called ‘the growing exaltation of the collective and the growing indifference to persons’ 28 was an increasing occupation with Lewis from the mid-1940s until his death. Indeed, his opposition to radical and utopian change moved him to write, ‘I am opposed to all very drastic and sudden changes of society (in whatever direction) because they never in fact take place except by a particular technique. That technique involves the seizure of power by a small, highly disciplined group of people’. 29

The proclivity of government to expand and even seize power is augmented, even animated, by governmental indifference to individual persons, in Lewis’s view. This found expression in the supposed compassion of the smothering welfare state. ‘Lewis regarded earthly socialism not as a remedy for the sins of capitalism’, writes Steve Gillen, but ‘as a far more dangerous alternative that vitiates individual responsibility by creating the illusion of Christian charity’. 30

Lewis gave voice to this not just in his commentaries but in his fiction. As Lily Glasner writes of The Chronicles of Narnia:

In a century characterized by a dismissal of solid values (moral and lingual) and shadowed by two World Wars, Lewis has recruited his knowledge of medieval thought and his force of imagination in order to reestablish a political message in the tradition of medieval writers such as Alan of Lille and Thomas Aquinas, in which the religious and the political realms are intimately tied. This political message promotes the leading of a life endowed with faith, courage, and goodness, towards that which it identifies as the ultimate end of human life: salvation. 31

Similarly, in his novel That Hideous Strength (in which, writes James Como, Lewis exposes ‘the particular ‘genius’ of (the 20th) century, a totalitarian death wish’32), Lewis shows deep concern with authoritarian politics which, by definition, exclude religiously informed virtue. The organization he called ‘NICE’ – the National Institute of Co-ordinated Experiments – is the central case in point. NICE was, Lewis said, ‘the first-fruits of that constructive fusion between the state and the laboratory on which so many people base their hopes of a better world’. 33

NICE represented the logical consequence of the state’s abandonment of unique human value. Toward the end of his life, Lewis wrote, ‘Classical political theory, with its Stoical, Christian, and juristic key-conceptions (natural law, the value of the individual, the rights of man), has died’. 34

Given his view of human fallenness and the persistent lesson of history that human pretensions of creating God’s Kingdom without God inevitably collapse, is it any wonder that Lewis would ask, ‘Have we discovered some new reason why, this time, power should not corrupt as it has done before?’

A final element of Lewis’s concern with state power had to do with the intellectual arrogance of whatever generation happened to be or be gaining in power. Lewis called this tendency ‘chronological snobbery’. In his memoir Surprised by Joy, he described it as the ‘uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited’. 35

Similarly, when a person gains a new insight, he sometimes believes he is the first person to whom it has occurred. His intellectual self-infatuation leads to unctuous pronouncements and airy condescension. Then he reads Plato or First Samuel or The Aeneid and realizes that maybe someone else had recognized it earlier. Lewis would agree that we must dash this conceit to the ground.

A Modest Dispute

There is much more to say, including Lewis’s reliance on John Locke and John Stuart Mill for some of what I have just described. 36 However, there is one component of Lewis’s beliefs about the danger of state power and the purpose of government itself that I must dispute.

The apparent libertarian bent of some of Lewis’s writings is most apparent to, of course, libertarians (just as his supposed quasi-statism is to Dr. Nicholson). In one sense, Lewis’s libertarian fans are correct: As noted earlier, he was horrified by government’s intrusions in private life. ‘Of all tyrannies a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It may be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies’, he wrote in 1949. 37

This theme permeates Lewis’s ongoing critique of the state. In one of his final essays, 1962’s ‘Sex in Literature’, Lewis writes that he regards ‘perversion, fornication, and adultery’ as ‘evils, but (the) law should be concerned with none of them except adultery’, as adultery is a violation of a legal covenant. 38

It is here I qualify my enthusiasm for Lewis’s political vision. This libertarian view of harm – if something does not immediately affect me, it should be allowed 39 – is too limited in its scope. Same-sex marriage does not harm individual, traditional marriages. However, it harms the institution of marriage and the development of children. These things are quantifiable. 40

Thus, personal preference should always and only be allowed insofar as it does not unweave the strong fabric of a healthy society. To take another example, alcoholism is not a victimless crime, a matter of transaction between the local liquor dealer and his customer. It destroys families. It reduces productivity at work. Its treatment escalates medical costs. And so on.

So, with Lewis, we must celebrate personal liberty. But such celebration must be qualified by the recognition that without personal moral and social self-government, without virtuous character, liberty eventually will descend into license. And as license becomes widespread, the fascism of which Lewis so often and eloquently warned will darken our culture with ever greater intensity.

God’s Triumph in History

With all of Lewis’s prophetic warning against the excesses of collectivism, statism, and progressive authoritarianism, he maintained a benign sense of hope concerning man’s future. And this is the third critical aspect of Lewis’s understanding of politics: All of human history, including our political endeavors, are being drawn to a conclusion controlled by a divine Sovereign.

‘As a Christian I take it for granted that human history will someday end; and I am offering Omniscience no advice as to the best date for that consummation’, he wrote a few years before his death. 41

It is in that context that Lewis warned rather extensively about the danger of historicism. He defined historicism as ‘the belief that men can, by the use of their natural power, discover an inner meaning in the historical process’. 42

This is significant, in that historicism intrinsic in the faith of modern progressivism. For example, President Obama referred frequently to the ‘arc of history’ and to the ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ sides of history. 43

Historicism argues that there is some unknown and unseen force guiding human life to ever better conclusions. The God of the Bible has no place in this conception, but it is nonetheless a deeply religious understanding of human history. As the social historian Herbert Schlossberg has written, ‘There is no way to escape determinism in the idea of inevitable progress’. 44

Historicism simply denies there a particular being doing the determining. It is predestination without One Who predestines.

This framework of understanding is, as C.S. Lewis recognized, pagan. It is the secular heresy of that progress – however that amorphous term is defined – will win out as if progress itself is a deity. It is a pathetic and unsubstantiated faith in human achievement without man’s Author and history’s Completer. Lewis said of historicism that it is ‘the belief that the scanty and haphazard selection of facts we know about History contains an almost mystical revelation of reality … it is wholly incompatible with Christianity, for it denies both creation and the Fall’. 45

But Lewis did believe in a God Who was sovereign over all history, over all the political strivings of man. He had faith in One Who would draw together the seemingly infinite number of its threads and, in the twinkling of an eye, weave a tapestry so glorious that we would look upon His eternally devised plan in wonder. Thus, Christians must raise their eyes to a greater kingdom than any earth can provide, a permanent and universal realm ruled in peace and justice by the One True King.

Lewis made no pretense of prediction. He expressed no conviction as to whether we are in the final days. His hope rested not in a projected date but in the God Who controls all dates. As Lewis wrote in his essay, ‘The World’s Last Night’, ‘We do not know the play. We do not even know whether we are in Act I or Act V. We do not know who are the major and who the minor characters. The Author knows’. 46

And because He knew that Author, Lewis could write in The Last Battle:

And as he spoke, Aslan no longer looked to them like a lion; but the things that began to happen after that were so great and beautiful that I cannot write them … for them it was on the beginning of the real story. All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story, which no one on earth has read; which goes on forever; in which every chapter is better than the one before.

Conclusion

The ‘enduring value’ of Lewis’s musings on ‘politics and natural law is not that he offered easy solutions to complex political questions’, write Dyer and Watson. Instead, Lewis ‘defended a compelling account of reality that could make sense of and account for the existence of reason, the freedom of the individual, and a kind of political rule that is not tyranny’. 47

This framework becomes evident by combing-through Lewis’s copious writings, which contain much about politics and man’s experience of civic life. His beliefs about political man are unsystematized. But they are emphatic, even if embedded incidentally his many books, articles, and letters, and also clear and consistent and grounded in faith in a grand divine plan. A plan involving the creation and fall of man, redemption in Jesus Christ, and culmination in the triumph of the Triune God. As Lewis reminds us, ‘The glory of God and, as our only means to glorifying Him, the salvation of human souls, is the real business of life’. 48

1 Quoted in Tim Scheiderer, ‘Lewis and Politics,’ August 23, 2018, in www.Narnia.com

2 See Dyer , Justin and Micah Watson, C.S. Lewis on Politics and the Natural Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 5-7

3 Justin Dyer and Micah Watson, ‘The Old Western Man: C.S. Lewis on Politics and Morality’. Modern Age 59:4 (Fall 2017), 28.

4 Dyer and Watson, ‘Old Western Man’, 28.

5 Lawrence Reed, ‘C.S. Lewis Saw Government as a Poor Substitute for God’, Foundation for Economic Education, December 19, 2018, https://fee.org/articles/cs–lewis–saw–government–as–a–poor–substitute–forgod/

6 Scheiderer, ‘Lewis and Politics’

7 C.S. Lewis to W.H. Lewis, 22 March 1940, quoted in John Wain, ’C.S. Lewis’, The American Scholar, vol. 50, no. 1 (Winter 1981), 75-76. Cf. Lewis’s 1940 letter to his brother: ‘The world, as it is now becoming and has partly become, is simply too much for people of the old square-rigged type like you and me. I don’t understand its economics, or its politics, or any dam’ thing about it’ (quoted in Dyer and Watson, C.S. Lewis on Politics and the Natural Law [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 5

8 ‘Finding the Permanent in the Political: C. S. Lewis as a Political Thinker’, July 15, 1995. http://www.independent.org/news/article.asp?id=1566

9 Mervyn Nicholson, ‘C.S. Lewis was a Red’, June 29, 2018, www.counterpunch.org

10 ‘I doubt if I am a Tory. I am much more nearly a political skeptic’. Lewis to J.B. Priestly, 1962, quoted in Dyer and Watson, loc sit, 6-7

11 Robert C. Stroud, ‘C.S. Lewis Versus Socialism’, in MereInkling.Net, August 9, 2016. https://mereinkling.net/2016/08/09/c–s–lewis–versus–socialism/

12 Ibid

13 C. S. Lewis, Letters of C.S. Lewis, ed. with a memoir by W. H. Lewis (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1966), 235.

14 Philip Vander Elst, ‘C.S. Lewis: Political and Cultural Conservative,’ Crisis, November 1, 1994. https://www.crisismagazine.com/1994/c–s–lewis–political–and–cultural–conservative; George Watson, ‘The Art of Disagreement: C.S. Lewis,’ The Hudson Review, vol. 48, no. 2 (Summer, 1995), 234.

15 Diane Kriby, ‘Christian Faith, Communist Faith: Some aspects of the Relationship between the Foreign Office Information Research Department and the Church of England Council on Foreign Relations, 1950-1953’ Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, vol. 13, no. 1, 230-231

16 ‘Equality’, The Spectator, vol. CLXXI (27 August 1943), p. 192. Reprinted in Present Concerns: Journalistic Essays, ed. Walter Hooper (New York: HarperOne, 1986).

17 C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (San Francisco: Harper, 2001), 56.

18 Benjamin Hutchison, ‘C. S. Lewis: Critic of Progressivism’, The Imaginative Conservative https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2018/04/c–s–lewis–progressivism–benjamin–hutchison.html

19 Dyer and Watson, loc sit, 63

20 Reed, ‘C.S. Lewis Saw Government’

21 ‘Democratic Education’, 34, in Present Concerns.

22 Lewis writes sardonically of Plato, ‘Mr. Joyce and D.H. Lawrence would have fared ill in the Republic.’ ‘Christianity and Culture’, Theology, 40:237, March 1940, 169 23 Mere Christianity, 40.

23 Mere Christianity, 95. Cf. Reprinted in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, ed. Walter Hooper (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 316.

24 ‘Willing Slaves of the Welfare State: Is Progress Possible?’ The Observer, July 13, 1958, reprinted in God in the Dock, 315. He had written something very similar 17 years earlier in his ‘Meditation on the Third Commandment’ (The Guardian, January 10, 1941): ‘On those who add ‘Thus said the Lord’ to their merely human utterances descends the doom of a conscience which seems clear and clearer the more it is loaded with sin’. Reprinted in God in the Dock, 198. 1941), 18

25 ‘The Poison of Subjectivism’, Religion in Life (XII: Summer 1943), reprinted in Christian Reflections (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 81.

26 History of Sixteenth-Century English Literature, Excluding Drama (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957), 46-50. Quoted in https://fpb.livejournal.com/621701.html

27 ‘Willing Slaves of the Welfare State: Is Progress Possible?’ reprinted in God in the Dock, 314

28 Lewis, ‘A Reply to Professor Haldane’, in On Stories: And Other Essays on Literature (Eugene: Harvest Books, 2002), 78

29 ‘A Reply to Professor Haldane’, in Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories (New York: Harcourt, 1994), 82.

30 Steven Gillen, ‘C.S. Lewis and the Meaning of Freedom’, Journal of Markets and Morality (12:2), Fall 2009,262

31 Lily Glasner, ‘But What Does It All Mean?’ Religious Reality as a Political Call in the Chronicles of Narnia’ Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, vol. 25, no. 1 (90) (2014), 69

32 James Como, ‘Mere Lewis’, The Wilson Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 2 (Spring, 1994), 116

33 That Hideous Strength (New York: Scribner Classics, 1996), 21

34 Lewis, ‘Willing Slaves of the Welfare State: Is Progress Possible?’

35 Surprised by Joy (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1966) 207-8

36 Dyer and Watson (loc sit, 103) note specifically that ‘Both Locke and Lewis believed that the end of government was the protection of individuals and their property, broadly understood. Bot claimed that God is the ultimate source or property, and as such, God is the ontological source of genuine morality’.

37 ‘The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment’, God in the Dock 292.

38 ‘Sex in Literature’, The Sunday Telegraph, September 30, 1962, reprinted in Present Concerns: Journalistic Essays, ed. Walter Hooper (New York: HarperOne, 1986).

39 For Lewis’s debt to Mill with respect to his understanding of the nature of harm, see Mill’s comments on liberty and privacy in On Liberty (London: John W. Parker and Sons, 1859), 26-27.

40 Pat Fagan, ‘Sociologists Mislead Supreme Court, Put Politics Ahead of Science on Same-Sex Parenting’, April 23, 2015, https://www.frc.org/op–eds/sociologists–mislead–supreme–court–put–politics–ahead–ofscience–on–same–sex–parenting

41 ‘Willing Slaves of the Welfare State: Is Progress Possible?’, Ibid, 312

42 ‘Historicism,’ Christian Reflections, in The Collected Works of C.S. Lewis (New York: Inspirational Press, 1996), 243

43 George W. Bush, Second Inaugural Address, https://www.bartleby.com/124/pres67.html; David A. Graham, ‘The Wrong Side of ‘the Right Side of History,’ The Atlantic (December 21, 2015) https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/12/obama–right–side–of–history/420462/

44 Schlossberg, Herbert. Idols for Destruction: The Conflict of Christian Faith and American Culture (Wheaton: Crossway, 1990), 19

45 ‘Modern Man and His Categories of Thought’, in Present Concerns: Journalistic Essays, ed. Walter Hooper (New York: HarperOne, 1986), 77

46 The World’s Last Night (New York: Harper One, 2017), 99ff

47 C.S. Lewis on Politics and Natural Law, 137

48 ‘Christianity and Culture,’ 167-168

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Regent University.